-

Life on a Community, pt. 2

After my weekend in London, I make my way back to The Community. But first, I look for a bag of coffee beans to give as a gift to the member who’s always sharing his French press with me. I end up in a New Zealand coffee shop that seems to be where all the Americans are hanging out—they even have an American barista in for the day. I linger in the city a little longer than I should—it’s easy to get distracted in London—and as I’m leaving find myself in a crowded station navigating a sea of West Ham United fans in the middle of a rail strike. I’ll spare you the ordeal of the train ride back.

Since the bus is out, I have to walk back to the Community from the station. It’s a little over three miles along a narrow road where the sidewalk is rapidly replaced by tall hedges that hug the asphalt. There’s not a good place for me to walk or even see vehicles passing around curves. I have to run through short sections of it and have to dive into the occasional bush. Eventually I end up crouching through a gap in the bushes and walk the rest of the way into town through the field of a much larger commercial farm. As I emerge back through the hedges onto the road, the plants take their revenge. I am coated with briars and burned by stinging nettles.

“I don’t even want to tell you what you missed,” one volunteer tells me the next morning. What I missed—what I had hoped to get back early enough to enjoy—was a roast pork dinner. A freshly butchered hog, killed that day, fresh garden vegetables, bread pudding, apple sauce.

I also learn that I didn’t have to walk along the road back from the station. As with my walk to Dedham the week before, there are a series of interconnected footpaths that lead you through the Dedham Vale. It’s apparently a beautiful walk.

Another volunteer tells me it’s karma for traveling on a strike day.

We spend Monday digging in the mangold field, listening to the steady boom of rockets in the distance.

Thus begins a more melancholy and subdued second week in the community—if only because there are fewer volunteers. The first week there’s an entire family of six volunteering together, and another five of their relatives show up mid-way through. In all, including myself, there are about fifteen “guests” the first week. Even though it’s the “quiet” time of year, when many people are away on vacation (if only camping in a nearby field), the community bustles with activity. But the second week, it’s just me, a prospective member, and a Marxist graphic designer who’s there for a “working holiday.”

* * *

I pay a few pounds for a copy of an oral history The Community has put together. There’s amusing details: decades-old photographs of people I now recognize, an infographic on a “communal flush” where everyone pulled the plunger on their toilets at the same time in order to clean out the pipes, and an anecdote from a volunteer describing rabbit hunting with the member I hunted rats with:

31st July 1998: Strange day. In the morning I was with F. hunting rabbits with ferrets. At the beginning it wasn’t pleasant but it was an ecological way to kill rabbits.

It also contains recurring sentiments from people who volunteer there:

- It takes a long time to understand the relationships here

- Not feeling at ease in the kitchen

- Unsure of what is OK and what is not

- No personal space to relax in

- Strong feeling of being an outsider rather than an insider

- The friendly welcome and warmth can give the impression that everyone here is wonderful all the time, which is not very realistic.

I feel kinship with many of these points. There’s a lot to learn and adjust to, and the community’s rhythm can disorient you further: everyone eating and working together during the day, and then disappearing to their private spaces during the evening. It can be simultaneously overwhelming and lonely, especially when you’re getting used to it.

Because of that, I’m grateful that one of the new volunteers (the Marxist on a “working holiday”) makes an effort to bond with me and the other guest. The first night we’re there together we take a walk along the footpaths in the nearby Dedham Vale, Constable Country. Around us is the land that John Constable, one of the most famous British Romantic painters, depicted in his art. Half a mile from this rural commune is an honest-to-God tourist attraction.

Our destination is the Flatford Mill, which was owned by Constable’s father and is the subject of one of his most famous paintings. Like much of his work, the human elements are dwarfed by the drama of the nature around them. Trees, clouds, and light appear to be in constant contrary motion. When we get to the mill, the sun is setting and the light is low. It’s calm, still. “I don’t think there was as much duckweed in the pond when he painted it,” one of the other volunteers comments. I snap a picture to compare it to his rendition when I see it in the National Gallery.

We take a different route heading back, but a bridge crossing is out, so we’re forced to take a much longer route back to the Community. In the moonlight, the prospective member tells us about her family. She has recently visited a much older brother who lives on the Isle of Man. He isn’t doing well; the nostalgia of her return is mixed with frustration and sadness over his slow decline.

She tells us about her trips there as a child: the ferry, walking paths that she imagined would be shorter now that she was traversing them on longer legs (they weren’t), and the island’s strange political history. It’s only recently they’ve stopped caning people, she tells us.

It’s true. The Isle of Man is not part of the United Kingdom, but instead something called the British Crown Dependency, and as a result maintains a greater degree of autonomy over its laws. So, while the mainland outlawed corporal punishment in 1948, the island continued beating people with birch rods into the seventies.

The Rt. Rev. Benjamin Pollar, the former Bishop of Sodor and Man had this to say in a newspaper article on the subject. “They’ve thoroughly deserved it. I am definitely in favour of the use of the cane and the birch. I have always held the view that for crimes of violence corporal punishment is a valuable deterrent. We need it more than ever now.”

So there’s that.

* * *

But conversations often turn to the grand and the personal whenever I’m with a smaller group—especially other volunteers. The first week, I went out for drinks with a few of them (to try genuine English bitter) and it’s not long before we’re going around the table saying whether or not we believe in God. The volunteer who’s considering joining asks the same thing. In her case, I’m less surprised because the last organization she had been a part of was more of a conventional commune, complete with a charismatic leader. It had become a little too cult-like, and the leader’s bad behavior was becoming impossible to ignore. So I don’t blame her for wanting to get her bearings on the situation before getting too involved. She tells me that she picked out The Community from those listed on Diggers and Dreamers because it seemed the most “normal.”

But other volunteers want to establish a bassline and there’s less risk with oversharing when you’re not going to see a person again after the two weeks you’re with them, and sometimes members like to complain about the community to people who won’t stare them down at the next weekly meeting. And then there’s our philosopher member who still wants to debate during the second week. He gets into arguments with the Marxist volunteer about all manner of questions. He’s more receptive to political violence, for example, especially because he’s less convinced that humanity has a tendency towards antagonism that it needs to overcome, but instead that the working class need to overthrow their rules. Later I find out that he works for his political party, explaining the eloquence that I’m initially in awe of.

I try my best to answer these questions when I’m asked them. I think it’s only fair if I’m going to be writing about my experience. But F. was right, when he said I was a guarded soul. My answer is usually something like: “I was raised Catholic, and when I was a teenager my parents started taking us to a Baptist church. Right now I’m figuring out what I believe. I’m seeing what else is out there, but I’m not sure what to think.”

* * *

Work remains much the same through the second week. We gather onions that had been ripening in a shed. We pick purple French beans that will turn green when cooked. We continue to water and weed the mangold patch. And we salvage what we can from the corn patch. The rats have won: anything that can be salvaged is plucked from the stalks, and everything else is fed to the happy cows.

But there are new responsibilities—and new people. One day we’re tasked with stealing as many of the pears from the wasps as possible. The member in charge is relatively new, and part of her responsibility is to decide which of the pear trees they would like to plant more of. Once we gather them up, we’re to separate them and sample them to help her make up her mind.

Part-way through we realize we need another ladder, and so we walk to the orchard to get one. She’s a forager, and so I tell about some of the unique things that can be found where I live in the mountains. She tells me that she recognizes plants here that she had encountered growing up in Nepal. She knows they’re good to eat, but isn’t able to identify them in English. A favorite of hers is a mushroom that strikingly resembles a steak when cooked. It even bleeds.

When we get back, she spreads a few slices of each pear on a plate and has us try them. She’s a little nervous because she’s relatively new to the community and this will be an early “big decision” that’s entirely hers to make. Although the pears all taste about the same to me (many of them not yet ripe), she seems to have come to a decision about her favorites.

She’s going down to the river with some of the other parents and their children, and she invites us volunteers to accompany her. I’m hesitant at first but end up going. It’s idyllic: fields of farmland subdivided by the more extravagantly vegetated river banks, where shade trees and tall grasses grow next to the shore. Everyone is excited about seeing swans, amusingly confirming a British stereotype I hadn’t expected to be true.

The Marxist volunteer talks me into taking the canoe the group brought down the river. He has an interest in the years surrounding the American Civil War, and—inspired by our canoe ride—recommends Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi. I, meanwhile, ask him about every nineteenth century European novel I can think of that has anything to do with socialism: “Have you read Germinal?”

“I actually read Germinal while I was working in a mine,” he tells me. It was another “working holiday,” this one clearing out debris from the tunnels so that the mine could be turned into a tourist attraction. The work ended up taking them much deeper into the mines than he and the other volunteers, mostly black French teenagers, had expected, and it was much more dangerous than they had expected as well, as they were forced to navigate around pitfalls deep enough to kill them. At one point he and the other volunteers confronted the man in charge. “We wouldn’t be doing this work if you were paying us.”

He acknowledges Dostoyevsky’s conservatism but counters: “Ah, but he gave the socialists the best lines.”

It’s nice being on the river, and I suppose this is part of what makes the community special. I imagine this would be true if I were to stay longer, if I were a permanent member: there are rhythms and routines to the community, a pulse that modulates with the time of day or the seasons, but everything is equally in flux. The melancholia will pass. Whatever you’re feeling, whatever is happening will pass. The community had a long history up to the moment I arrived, and it will continue to change for as long as it exists after I leave.

* * *

A few days before the end of my stay at The Community, I attend a small Quaker meeting that’s held on the outskirts of the dining area. I double-check with the organizer to make sure it’s okay for me to be there. I don’t want to intrude on anything private, but I do have a genuine interest in participating.

We all gather together a few hundred yards away from the dining area. We’re offset from the building by ancient trees and vegetation, and the atmosphere is very much like one of Constable’s paintings: all dramatic light and trees in motion from a high wind. The organizers for the meeting have arranged ten red stackable plastic chairs in a circle and laid out a few books that describe Quaker values on small tables.

After a brief introduction, we all sit in silence. The structure of any Society of Friends meeting is that everyone is supposed to sit without speaking, but if you feel compelled to say something you’re supposed to share it with the group. No one does. For forty-five minutes we all sit there together, listening to the wind in the trees, children playing in the distance, scattered conversation, and people washing pots and pans after dinner. As much as I would like to have a transcendent experience, I don’t have the right disposition for mysticism. I can’t be Annie Dillard receiving a vision of the baptism of Christ on the shore of the pacific ocean. The moment is peaceful, and I’m trying to regulate my breathing and slow my heart rate—but that’s it.

When our time’s up we chat briefly together. One of the members mentions that she finds the book beautiful, but she thinks she would like it better if it didn’t mention God.

Inspired by this, I share my own doubts, my own desire to search for an idea of God that makes sense to me and the juvenile rebellion I have to fight any time I’m confronted with something religious.

The organizer tells us that Quakerism is essentially a set of values. In the UK it’s a leaderless organization and it draws people from all walks of life. There are Buddhist Quakers. Atheist Quakers. At its core it’s about an understanding of something larger existing outside of (and within) yourself, about engaging in a set of values and practices that reflect that.

If I’m going to expand this anecdote to what it means for the community as a whole, I’d say this: One of the debates around communities like this is that you need some sort of higher power guiding your actions, otherwise the whole thing will fall apart. I’ve read this in both literature about intentional communities and I’ve heard it from religious groups who share everything in kind: you need to believe in God for it all to hang together. A philosophical or political or environmental position isn’t enough. And while it’s true that many experiments in communal living—almost all of the communities that sprung from the back to the land movement—ended in failure. In her book Heaven is a Place on Earth, writer Adrian Shirk suggests that failure is inherent to any utopian project. The whole point is to try new things, to experiment. These experiments will inevitably lead to the dissolution of whatever project you’re engaged in, but that’s better than getting stuck, becoming calcified. But this community has persisted for fifty years. Fifty years of people deciding they all want to live in a big house together without any religious convictions tying them together. The values guiding that decision may be personal, and they may have shifted over time, but it hasn’t changed the overall structure of the project.

* * *

Before I leave, I make the rounds of saying goodbye. People share phone numbers and email addresses and tell me that I can be their guest if I’m ever interested in coming back. I write a message on a chalkboard thanking everyone for their hospitality.

On my last night, I’m trying to finish up a book that one of the members has loaned me, The Third Policeman. He had given it to me after I’d expressed admiration for mid-century British experimentalists like B. S. Johnson and Ann Quin.

Another volunteer joins me in the loft-like dining area connected to the kitchen. He’s going to be up all night studying for a certification test the next day. And as we’re sharing each other’s company, he offers me a beer from his private stash, and we talk about how he doesn’t trust his phone not to listen to everything he’s saying, about his ex who still lives on The Community.

He tells me that the member who loaned me the book doesn’t have many friends in the community, and that he mostly hangs out with volunteers. This saddens me, because I’ve enjoyed spending time with this member. He’s been kind and generous in every interaction I’ve had with him. But I also suspect that what this volunteer is telling me is not entirely true. He still contributes to the farm, and he seems happy to be around so many people, especially the children, who seem to serve as surrogate grandchildren for him.

That’s the shape of most stories, right? You start with a simple question and end up embracing the muddle and complexity of where looking for the answer takes you.

-

Thanet Tape Centre @ Café Oto

When I was involved with college radio, there were a few labels I could reliably count on for providing interesting music. One of those was Otoroku, a label I initially wrote off because I found out about them through their reissue of The Topography of the Lungs, which I had head described as “the worst album ever.” But I gave it a second chance when Rachel picked it out from the library for a show, and I ended up digging into everything they had to offer, particularly some of the live shows featuring performers like Alexander Hawkins and Akira Sakata backed with the Turkish free jazz outfit Konstrukt. These were recorded at the label’s venue, Café Oto.

Thanet Tape Centre, meanwhile, I knew about through the label’s founder Benedict Drew, who makes agitprop-ish visual art—politically obvious, but gaudy and sickly enough to be surreal and compelling. He also put out one of my favorite albums of 2017, Crawling Through Tory Slime. Which, again, is politically obvious, but surreal and compelling.

So a show by Thanet Tape Centre at Café Oto was something I sought out for my weekend in London, naturally.

The venue is a moderately-sized space in Dalston, a neighborhood, like many immigrant or working-class neighborhoods in London, which is in the process of gentrifying. There’s still an open-air West Indian and African Market a couple blocks away, but it’s quote-unquote hip enough that members of The Community heard that Italian Vogue had called it London’s “coolest venue” a decade ago, which I thought they were joking about until I looked it up. (“That was a while ago. It’s probably not cool anymore.”)

Said Stuart Lee (who is allegedly a regular, at least around 2012) in a Guardian article about it: “The vibe is functional and no-frills … rather than the ersatz no-frills vibe that tossers with too much money aim for in trendy spaces. It’s what Yanks tell you downtown NY is like but actually isn’t. It’s what I dreamed London would be like, and what it was a bit like in the 80s.”

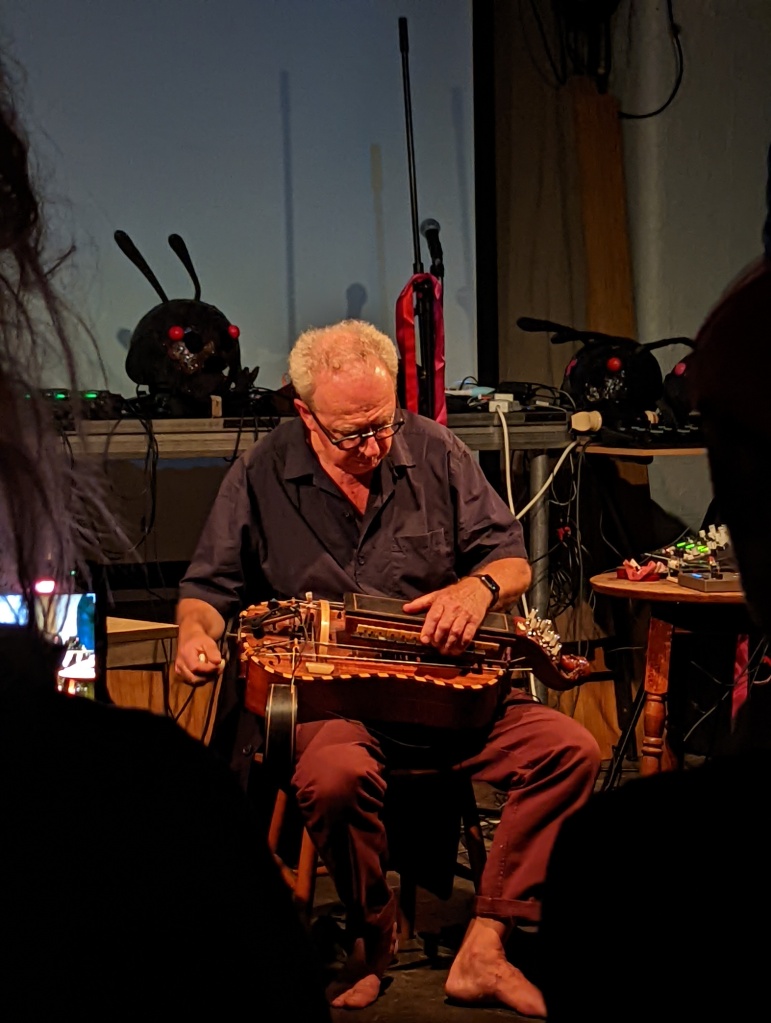

The show was a much delayed celebration of the label’s first release, Jem Finer’s Hrdy-Grdy, but we opened with an invocation from Arianne Churchman. She performed on a harp which featured a horse head protruding out of it. The horse’s mane covered the strings, and she spent the first several minutes of her performance singing a cappella while she tied scraps of paper into the mane.

Arianne Churchman Finer, when he took the stage alone with his hurdy-gurdy, began with what sounded like a folk song. It was slightly rough hewn, not always perfectly in time, but was ultimately intended to set the scene, to envelop the audience in the instrument’s incantatory drone. For the rest of his set, he explored the sonic possibilities of his instrument, warping the sustained ringing of the strings by twisting the tuning pegs or manipulating elements normally tucked away under a wooden cover. (I’m not familiar with the instrument, but he often did things with it that it didn’t seem like you were “supposed” to do. I could be entirely wrong.) For other parts of the set he would loop fragments of sound or filter the instrument through a series of small electronics to give it an otherworldly quality.

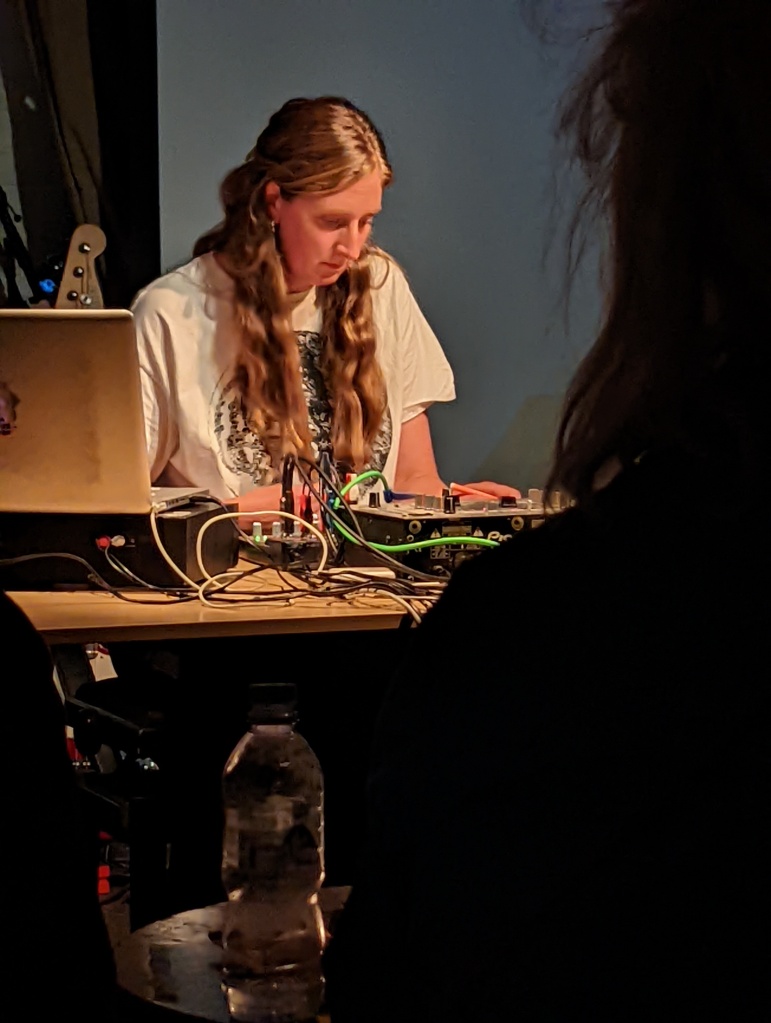

Jem Finer By the time he was finished, the audience was primed for the strangeness that was to follow. Up next was Rebecca Lee, who performs under the name Bredbeddle, making music out of the stuttering fragments of sound captured live on a couple of turntables. The raw audio is fed into into her laptop, which is then manipulated and layered into a complex collage of skips, crackles, and fragmented audio, particularly from English folk or classical records. Every now and then she allowed a sample to play out for a minute or two, a lone voice singing or a conversation between two people, which would float eerily on top of everything else until it was cut off mid phrase. The samples were largely generated by Lee nudging the needle of a turntable with the eraser end of a pencil. For the rest of the time, she kept the pencil balanced between her lips and looked with concentration at her laptop screen. People like to complain about artists who perform like this—it’s not visually interesting the way a virtuosic rock band or jazz ensemble is—but the result of her work was spontaneous and enveloping.

Bredbeddle The concluding act was Plastique Fantastique, an ensemble of musicians all wearing termite masks. Behind them was a screen of blaring strobe effects, convenience store chyrons, and stock photos from a late capitalist hellscape. The music itself, mostly composed of electronics, moved at a slow, building pace, with heavily distorted vocals on top of it. The singer’s voice had been digitally manipulated to such a high register that it was often difficult to make out about what she was saying most of the time. It seemed like most of it had to do with the collective efforts of these termites. While the musicians performed, one of the members of the group gathered up stalks of wheat that had been placed around the audience. For the finale, the audience was served slices of a vegan cake.

Very apropos of what I’m working on. Lots to think about.

Plastique Fantastique -

Life on a Community

There’s a chalkboard in the kitchen, and every morning at 9:30 the volunteers gather around it to find of what we’re going to do that day. Each member of The Community has a specialty—some tend to the animals, some keep honeybees, some look after a specific crop—and our job as volunteers is to help individual members with their work. At this time of year it often involves some variation of weeding or harvesting, but the tasks are varied, and there are many things that need to be done.

Most of the volunteers don’t have much experience doing farm work, although many of them have been here before. There are people here on “working holidays,” people looking to travel and see a bit more of the local color than they would at tourist destinations, and people who are interested in becoming members. I meet an abstract expressionist painter who lives just south of here, a French medical student, and a German salesman who brought his entire family with him. He has been visiting The Community for the past nineteen years. There’s also a writer who “would really like for people not to feel like they’re under the microscope—I’m not a journalist or a formal researcher or anything, just—”

When asked, sometimes it takes me a minute to explain what exactly I am doing here.

Example:

“Where are you from? Car-o-liney?” Then, when I’m asked about my program and some of my professors, I’m told: “It’s a shame lecturers at Universities aren’t known these days.” He says they tend to hide in their ivory towers.

(While we’re at it, here’s a few more examples of British condescension:

“Americans don’t know anything about cheese,” while gesticulating squirting squeeze cheeze on a cracker.

“Who would I know where you’re from?” “Do you know Dolly Parton?” “I do.” “She has a theme park near where I live.” “Does she really?”

“I saw the smugness in your eyes when you were talking about air conditioning.”

etc.)

And then from there I explain the details of the travel fellowship.

On my first day, I wake up at dawn, convinced that I’ve somehow slept through my alarm and I’m already an hour late. The assignment on the board is to help one of the members hack apart a tree that’s growing close to the building. The property is old—it dates back to the eighteenth century—and is pleasantly overgrown with vegetation. A cascade of vines overhangs the entrance to the kitchen, and the beds around the house are a mix of deliberately arranged flowers and shrubs and plants left to grow wild. This becomes a problem when creeping tendrils displace shingles on the roof or roots start to crack the foundation.

Our particular tree is scrubby and only slightly taller than a person, with nettle-like leaves and very hard vibrantly-colored wood, the kind of yellow-green hue that you usually only see on safety equipment and tennis balls. We work slowly with hand tools. While we do this kind of maintenance work over the course of my first week, I start to get the feeling that the plants have a mind of their own. When I’m hacking at reeds and bramble, when I feel the burn of stinging nettles, when thorns tug at my clothing, when a weed breaks in half when I’m trying to pull it up by the roots, I think: “They know exactly what they’re doing.”

* * *

Monday’s task simply says “sweet corn”; we’ll be helping an eighty-two-year-old philosopher with his crop. Within minutes of meeting him, he asks me to “tell him something transcendental” and lets me know that he can tell I’m a guarded soul. He explains that what we’ll really be helping him do is trying to keep rats from eating the corn. He claims to have spotted no fewer than two hundred of them crawling out of their hiding places and terrorizing his crop, gnawing on as much as fifty percent of their daily harvest. (His partner lightly slaps his arm when he says this and tells him not to be so Latin American, although one of the volunteers corroborates that rural brown rat colonies can have up to a couple hundred members.)

We start by walking around the perimeter of a fence line that encircles two coops where The Community used to keep turkeys for their Christmas dinner. This is picked as a likely spot for the rats to hide. We’re told to use our imaginations when looking at patches of flattened grass or gaps in the wire fencing. One of the volunteers is skeptical, but we clear out the tall reeds and brambles that have grown nearly four feet tall in the year the pens have been neglected in the hopes of drawing them out.

In The Blithedale Romance, the narrator, Miles Coverdale, himself a member of a transcendentalist community, doubts that it is possible to be a farmer and a poet at the same time:

It is very true that, sometimes, gazing casually around me, out of the midst of my toil, I used to discern a richer picturesqueness in the visible scene of earth and sky. There was, at such moments, a novelty, an unwonted aspect, on the face of Nature, as if she had been taken by surprise and seen at unawares, with no opportunity to put off her real look, and assume the mask with which she mysteriously hides herself from mortals. But this was all. The clods of earth, which we so constantly belabored and turned over and over, were never etherealized into thought. Our thoughts, on the contrary, were fast becoming cloddish. Our labor symbolized nothing, and left us mentally sluggish in the dusk of the evening. Intellectual activity is incompatible with any large amount of bodily exercise. The yeoman and the scholar—the yeoman and the man of finest moral culture, though not the man of sturdiest sense and integrity—are two distinct individuals, and can never be melted or welded into one substance.

Experience shows, however, that it is entirely possible to be a philosopher and a laborer. As we work, the member we were helping would occasionally pause and ask us an abstract and high-minded question: whether the natural state of humanity is flux or stasis, or the difference between an artist and an artisan, or if we as a species are predisposed to antagonistic action.

(So far, my main encounters with antagonistic action in the UK is that it’s my habit to veer to the right to make way for someone on the sidewalk, but here people tend to veer to the left.)

We spend two days hunting rats unsuccessfully. We clear out the pens, and then our boss storms into the coop, stomping on the straw-covered floor and shouting, “Rats, come out!” No rats come. The volunteer who informed us of the size of rural brown rat colonies lets us know that when farm workers wore bell bottoms they would tie string around their calves to keep rats from running up their pant legs.

When we’ve finished searching the pens, we investigate one of the wood piles. There are a number of them of varying sizes around the community, including a stack rough-hewn trunks. This will be fed to “The Dragon” in winter, a hulking green device that burns biomass and supplies some of the rooms in the community with heat. We find a number of potential tunnels in one of the piles and plug them with logs, but the next day even more corn is taken.

You may ask, why not poison the rats?

The Community was formed in the mid-seventies, and I believe the impetus for their founding was similar to the many other back-to-the-land communities that popped up around the same time: they were socialists and protesters, exhausted from the sixties, who felt that retreat was the best option. However, although it was considered a “middle class fad” at the time, the goals have shifted heavily from explicitly political retreat to ecological sustainability and organic farming. So in the case of the rats, they did decide to put poison by the chicken coops (another likely spot), but the poison is slow-acting—it can take up to two weeks for them to see any results. And after the decision is made, you can hear some of the members discussing the consequences, wondering whether or not the poison will travel up the food chain (at least for this type of poison it doesn’t seem to be the case). There’s a general reluctance to kill anything here. You make your peace with the spider on the rim of the sink at one in the morning. They don’t use pesticides or herbicides, and they rarely make use of any large-scale mechanized farming equipment. They try to disturb the land as little as possible, and are working to disturb the land even less.

In my time here, I’ve come to appreciate how vibrant and complicated everything is. Even in the midst of the heat and drought, the land provides abundantly. We’re just managing small pieces of it, nudging the system in certain directions, folding it back into itself. After they’re culled from the garden, the bodies of weeds serve as mulch for the crops. “They’ve taken nutrients from the soil, and it’s only fair that they give it back.” At this time of year, almost all of the food we eat is produced here. There’s sweet corn, beets, carrots, cabbage, tomatoes, aubergines, French beans, blackberries, and raspberries. Things I’ve never encountered or heard of as well, such as green gages, which are fruits the size of a large grape with a pit in the center. Purslane is sometimes plucked from wheelbarrows full of weeds and used in salads. We eat almost all of our meals outside with mismatched plates and cutlery. Food scraps are composted, and no one uses napkins.

In the case of lost corn, they are not interested in fighting back aggressively, scorching the earth to get rid of the pests. The rats have not abated, and they may be in cahoots with pheasants. By the second week, it’s decided to harvest as much of the corn as possible (rather than only retrieving a barrow-full or two a day) and to chop down the stalks when we’re finished.

The member in charge of the sweet corn is largely accepting of this result. Although it seems frustrating for him to give up so much of his crop, he notes that this is also one of the biggest yields they’ve ever had. And even a discarded stalk has value: once we hack them down, we feed them to the cows. They literally gallop when they see us coming.

After we harvest the corn, we shuck it (a word I taught them), and sometimes scrape the kernels off the cob. Most processing work needs to be done indoors, however, especially for anything sweet. Otherwise, you’re besieged by wasps.

Throughout most of the year, they’re useful at controlling the population of insects and spiders, but now the queen has effectively closed the hive in preparation for her hibernation, and thousands of wasps are belligerent and out of work. Their main pastime is to get drunk off the fruit of the land, either by swarming around apples and pears that have been pecked by birds, alighting on rotten fruit that has fallen off the tree, or swarming around us when we’re chopping something at a picnic table. A tiny bacchanalia that plays out around our humble labor.

* * *

Established in the mid seventies and composed of around fifty current members, The Community is one of the oldest and largest farms of its kind in the UK (excluding religious communities like the Bruderhof). The exception might be the Findhorn Foundation up in Scotland, which has significantly more members, but is also more commercialized. Visiting Findhorn often involves attending an expensive retreat. This community is very much a functional farm, and there’s little “profitable” activity here; excess produce is left outside the gate for £1 per bag.

All of the members live together in an old, sprawling building that has been added to significantly over time. In the eighteenth century, it was a private residence, first a moderate manor hall, then expanded to something larger because the owner had twelve children. After that, it became a convent, which is what it remained until the Second World War. This is the portion of its history I hear the most stories about, especially the sharp (often brutal) class distinctions between the higher and lower ranks. Lower-ranked nuns lived in small cells with slits in the doors to monitor their activity. There was a network of bells between the rooms that allowed senior nuns to summon others to their rooms. In the chapel, the choir benches for the abbess had two heading systems underneath. The bench for the novice nuns had none. The conditions were poor enough to inspire a book about a nun fleeing her captors.

Then, after the war, monks arrived who: “partied for twenty years and then left.” Brewing was a big part of what they did there. Sometimes artifacts from their time still show up when community members till the fields.

And of course things have changed further since the building became a community. Decisions for the whole of the community are made by consensus, but everyone has a large degree of autonomy over “their” part of the building. So things like hot water heaters and central heating arrived piecemeal. Even in an intentional community, people have their limits for how far they will trust the other people there, for what they are willing to risk or give up.

As a volunteer, I get a good sense of what day-to-day life is like here (at least in the summer), but I’ve only heard hints of the broader social dynamics.

I’ve been told things like: “If you hang around here long enough, you’ll have plenty of material for a novel.”

Conflict is supposed to be mediated by a third party, but feuds can last for years, and sometimes the situation resolves itself when one of the members decides it would be better to leave. I don’t know enough to speculate further—even on the scant details I’ve learned, and it isn’t the place of this blog to make conjectures about what things are really like here. You’ve probably noticed that I’ve been pretty coy about a number of aspects of The Community. I was asked not to include its name or the names of any of the members or include pictures. Some of this is for basic privacy reasons, especially for the children who live here or for people who work in healthcare and don’t want their address publicized. But it’s also to make sure the experience is as “true” as possible, even if it means leaving out certain details in this blog.

Besides, I’m much more interested in witnessing the day-to-day life of the place than trying to uncover some “dark secret” about what it’s “really like.” Conflict seems inevitable among groups of forty or fifty people living under the same roof. And it’s to the community’s credit that it’s persisted as long as it has and that there are people interested in moving here—including young people and families with children. There are few comparable models in the States. Most communities dissolve.

I wonder how much of their success has to do with the fact that it’s not a closed system. While much of what happens here is done communally—meals are eaten together, for instance—not everything is. People have one or two aspects of the The Community that they’re in charge of and they manage these tasks more-or-less independently. In the evenings, members disperse to their own units. Children attend the local school. Most people have jobs in the area. And while much of the food they eat is produced there (including milk, cheese, and meat: animals are slaughtered and butchered on site), they don’t shy away from purchasing outside goods, especially in the winter. (“We don’t want to live off exclusively potatoes and kale.”) It’s been a difficult summer between the heatwaves and drought, but there’s not visible panic about low yields the way you might expect if a poor crop meant starvation come winter.

* * *

“Are there any ghosts here?”

“You’re asking the wrong person. I’ve felt things here, but I haven’t seen the kind of physical presences that other people claim to have encountered.”

We’re standing in the kitchen sharing a bottle of wine that has been given to us by one of the members after we helped him disassemble a tent and relocate a massive cast iron fire pit.

If there are any vengeful spirits here, it may have been because of the irreverence the original members dealt with anything religious on the property. When the founders first moved in, they gutted the chapel. It’s now used as a playroom, with children’s toys strewn across the floor while a religious mural watches from the shadows on the far wall. There are other reminders that we’re in a former Convent: stained glass can be found in lots of unexpected places. And there’s an air of gothic gloom, especially when you start to notice all the cobwebs that can be found along the high ceilings. It’s “the sort of house that must have children, many flowers, open windows, and little vistas of bright things, to make it seem a joyous home.”

And it does have all these things. During the first week, there are more than a dozen children running around. And while much of the house is off limits to me as a visitor, I often stumble into unexpected beautiful spaces. A large room with bay windows and pink walls, a staircase with a skylight that leads to a section of the house where members live. Tonight especially it’s lively, with multiple pots of food bubbling on the stove and pre-war jazz playing on the speakers. It’s the French medical student’s last night and she’s making the entire community beef bourguignon. She and another volunteer had to peel an entire bag of potatoes for the gratin. All throughout the evening, people approach her to compliment her on her dish.

It’s in these moments that I really get the appeal of living here, what draws people to this lifestyle. And even outside of the dramatic gestures, people can be surprisingly generous. Most of the members drink tea, which is set up at a station in the kitchen, but one of the members is always offering to share French press pots of coffee that he makes from his own beans. I’ve been given homemade elderflower champagne. I’ve been shown family heirlooms, a handwritten playlet from the late nineteenth century passed down through one of the member’s family.

You can see why people come back, you can see why people stay.

-

Essex Man

The second day of my stay at The Community (capitalized but left unnamed; more on this in a future post), I talked to one of the locally-based volunteers in an attempt to situate myself in this part of the country. I’d learned from Theroux that there’s an oral tradition around various locations in the UK—people often have very strong opinions about places they had never been, at least according to him, and I wanted to see how much this was true. By complete serendipity, I saw an article about an exhibit at a nearby art gallery in Colchester, Firstsite, which explored one of the most infamous local figures, Essex Man. I asked the local volunteer about it.

“You’ve heard of Essex Man?”

“Well I wanted to check out some of the local history. We’re in Essex here, right?”

“Suffolk, actually. We’re right along the border. The river cuts the two counties in half, but people on the Essex side often claim they live on the Suffolk side. Essex has a pretty miserable reputation.”

Getting to Colchester without a car wasn’t easy. The direct bus doesn’t run on Sundays, so I “was forced” to walk along a series of scenic footpaths through the English countryside to a small village called Dedham. Unlike the US, where the majority of walking/hiking paths can be found in public parks, the Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty in the UK consist mostly of private property, with public footpaths bordering and intersecting pastures and farmland. Dedham boasts a six hundred year old church and a five hundred year old tea room. Puritan dissidents led by John Rodgers fled the village in 1635 and ended up in the Massachusetts Bay Colony; the area they settled, just outside of Boston, still bears the name Dedham. Spending time here, you run into a lot of the places that leant their names to towns and cities in New England.

A long wait in the tea room and a short bus ride later I was in Colchester. It was once called Camulodunum, and it was the provincial Roman capital of Britain. Remnants of this history are wedged into the structure of more “contemporary” architecture. Stone is scarce in the region, so Colchester Castle is built on the foundation of a Roman temple. The volunteer I spoke to said that the Romans planned on coming back, so they buried their belongings when they fled, and every now and then someone digs up their treasure.

The beautiful old architecture (largely spared from the blitz) cannot hide the creep of modernity. There are not one but two American candy shops. The Community members are exasperated to hear this when I return. I buy some Twizzlers and a Moon Pie to remind me of home.

In the lobby of Firstsite you meet him. Eight meters talk, thick neck, ill-fitting suit, pint of lager gripped in his hand. Cousin to Loadsamoney. Thatcher’s bruiser. The Essex Man.

Michael Landy, Essex Man (after Collet) Since the time of the Romans, the reputation of Essex has changed dramatically. It’s home to London’s nouveau riche. It’s known for gaudy houses with lions at the end of the driveway. There’s a long-running reality show called The Only Way is Essex that draws heavily on the stereotype. Even the local accent reflects this. The stereotypical Essex accent retains much of the quality of an East London working-class accent, except every word is deliberately enunciated. The forces of capital overthrowing the aristocracy, and everyone feeling that it’s incredibly tacky.

But there’s also something of a sacrificial landscape here, like the land bordering the oil refineries on the Louisiana delta or the people who have to live down wind of North Carolina hog farms. There are a number of landfills here. London used to dump its trash in the estuary. There’s an arms testing site, too. Working in the garden at the Community, you can hear the distant rumble of explosions from miles away, too evenly spaced and too consistent to be mistaken for the sound of thunder.

The broader consequences the British Empire were explored in the second exhibit by the Singh Sisters. Outside the exhibit proper, the museum displayed reference material for their work, Indian textiles, the fantastical and unreliable travel narratives of John Manderville, and an account of a slave rebellion by the Dutch soldier John Gabriel Steadman, along with other ephemera, like an image titled “The Graces in a High Wind.”

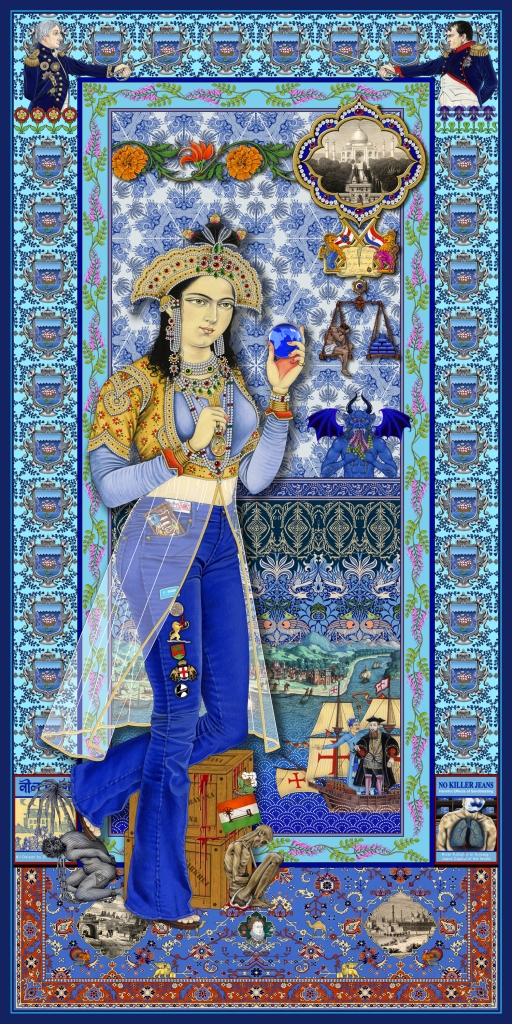

These influences were incorporated into complex collages, which were digitally printed into textiles and hung with backlighting so that the work glowed as if it were stained glass. The pieces, while often beautiful, were rarely politically subtle.

The Singh Twins, Indigo: The Color of India

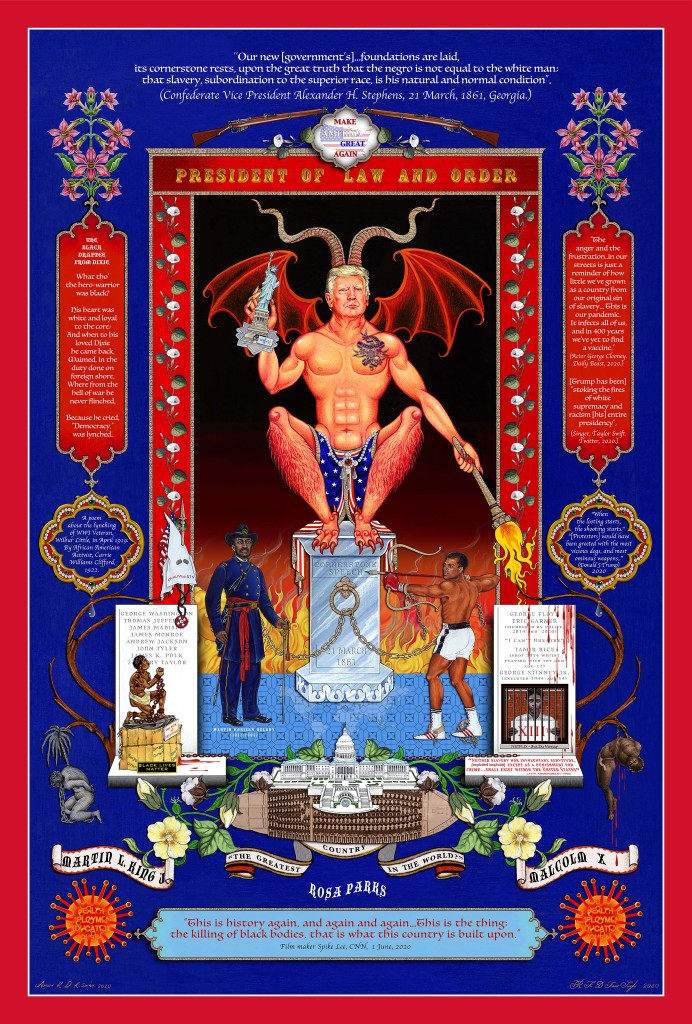

The Singh Twins, GET YOUR KNEE OF OUR NECKS There’s a side of American history that slowly emerges if you spend enough time looking. There’s the romanticized events and noteworthy atrocities they teach in school, but over time moments of strangeness, beauty, and shocking and banal cruelty emerge out of the conventional narratives. The UK—and the long decline of the British Empire—has a parallel history, which is much more visible when you’re actually there. Essex Man is the symbol of a regressive conservative government, but it’s also a snobby caricature of a people refusing to stay in their place. In an interview shown alongside the exhibit, the author of the original “Mrs. Thatcher’s Bruiser” article where the image first appeared comes across as elitist and posh. Likewise, the Singh Sisters clearly lovingly poured over the materials that influenced their work, and they highlight the beauty and humanity in these original pieces—even if the result is a tapestry of Donald Trump as the Devil.

-

The Nation’s Most Treasured Dish

About a third of the way into my flight across the Atlantic I thought to myself: “I’m about to run a marathon and I’m completely unprepared.” I’ve never really travelled outside of the country before—certainly not like this. For roughly the next five and a half weeks I’ll be making my way around the United Kingdom (and a little bit into Europe) to research intentional communities for a novel and to consume as much “general culture” as I possibly can.

I felt a little more sure-footed once I arrived in London. This isn’t so intimidating. A Five Guys and KFC greet you just across a busy intersection outside the entrance to the Liverpool Street Station. It’s just another Americanized city, not unlike Boston or New York, except everyone’s younger and all the restaurants are playing techno. (Check back in a few weeks to see how this perception changes.) The feeling goes away quickly once you get on a train to leave the city and start seeing the names of local gas station chains.

* * *

The stereotypes about the English countryside have not matched my experience. For about half of my trip I’m staying in the south-eastern portion of the county, in Suffolk and down a little into Essex, roughly “East Anglia.” It’s the driest part of the United Kingdom—someone I spoke to said it literally qualified as a desert—a condition exacerbated by drought and heatwaves. Temperatures hovered around 30C (roughly 85–90 degrees Fahrenheit) the first week I was there, which was stifling in the 15th century cottage I stayed in during the initial leg of my trip. It is neither cool, nor damp, nor hilly, nor green.

Trees here are gnarled and stocky. Hedgerows with sturdy leaves fight futilely against the sun. Ambitious gardeners plant sunflowers and roses. The fields are parched and grass is mostly dead. “It’s usually greener here,” I was told.

The view of the burial mounds at Sutton HooSuffolk abuts an uncharacteristic coast as well. Paul Theroux in his book The Kingdom by the Sea, describes it like this:

At the bottom edge of Suffolk, the coast collapsed in a mass of marshes and estuaries. There was no coastal path. Strictly speaking, there was no coast, but only forty miles of low waterlogged land, and isolated towns at the end of long flat roads. It corresponds to the complexity of the Scottish coast at the opposite end of the county, except that this was not sand, not rock, and instead of surf whipping into cliffs, this had a shallow sinking look.

Where I am, the evidence of the sea is present, even if you can never quite believe you’re that close to the coast. Silt and sand dominate in the thin dry soil.

The coast by the Woodbridge Tide Museum * * *

For the first five days of my trip I stayed in Raven Cottage. It had once been part of a medieval hall before being subdivided into smaller units. The interior is composed of irregularly spaced dark wooden beams, with hard plaster filling in the gaps. Photographs included in the welcome binder showed how these bones were excavated from under layers and layers of drywall.

At the top of the stairs sits a shelf almost half full of books of local history. One of the aspects of this country that is helpful to a traveler but frustrating to a writer hoping to say something original is that the land and its history have been so obsessively documented. It’s difficult to imagine an Airbnb in America where there’s a laminated piece of paper letting you know that your rental was built in 1465 from a parcel of land sold by John Raven. Titles on the shelf include: The Companion to East Anglia by John Seymour, A View into the Village: A Study of Suffolk Building by Erie Sandon, and Discover the Suffolk Coast by Terry Palmer. There’s a book on Needham Market Pubs. There’s A Suffolk Childhood, Suffolk Summer, and A Suffolk Christmas—all by different authors.

It’s also the setting for W. G. Sebald’s book The Rings of Saturn (not present on the shelf).

It’s not new to note how well-documented the county is, either. Theroux includes a list of similar travel accounts at the start of his journey. Within the first 50 pages of T.K.B.T.S. he meets up with another writer who is making an almost identical journey around the coast, only moving counter-clockwise instead of clockwise and travelling by boat instead of by foot and train.

For my purposes, the documentation is helpful—and much of the history is genuinely interesting. I took a walk down a narrow well-trafficked road and ended up at Sutton Hoo, a seventh-century burial site for an Anglo-Saxon king.

The Tudors seem to loom large. I visited a thousand-year-old mill with a wheel that turned with the ebb and flow of the tides; it had been in the hands of Augustine monks until Henry VIII took over the church of England. On a trip up to Framlingham castle, I learned the fortress had been used by Queen Mary in the battle for succession following the death of Edward VI. Thomas Howard, the Duke who arranged for Henry to marry two of his nieces, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, is buried in St. Michael’s Church, just below the castle, as is Henry’s illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy.

Recreation of a helmet found at Sutton Hoo, likely belonging to King Raedwald of East Anglia

The tomb of Henry Howard

St. Michael’s Church

Framlingham Castle * * *

At the start I was almost always by myself. I mostly only talked to someone if I was giving them money. For the next two weeks, I’ll be living on an intentional community of about fifty members and several volunteers. Afterwards I’ll be staying in student housing in London, followed by a few days in a sort of rebranded luxury apartment complex called “The Collective,” which seems to have filtered the language of back-to-the-land communitarians into a marketing ploy for a high-end dorm. (We’ll see.) For the last two weeks I’ll have a travelling companion, Rachel. But at the start I did a lot of eavesdropping.

I spent Friday afternoon at a laundromat in Ipswich where the owner and one of the customers, a woman who works for a leprosy charity, held forth. They talked about all the current problems, about how miserable the weather is, fuel and food prices, global warming, how the earth is slowly drifting towards the sun. “It’s stuff to moan about,” the owner said. “The English love moaning.”

She told the woman washing her clothes about a conspiracy-theory-loving taxi driver she likes to have conversations with. Apparently, between the two of them, they have the solutions for everything. “Frequently we sort the whole world out,” she said.

Likewise.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.